Guerrilla Marketing Was Never About Selling

How a new generation turned street tactics into anti-billionaire art.

Rossella Forlè, Founder We Hate Pink

Guerrilla marketing was never meant to be polite. When Jay Conrad Levinson coined the term in 1984, borrowing it from guerrilla warfare, he wasn't describing glossy activations or branded pop-ups; he was describing asymmetry. Small players using surprise, mobility, and audacity to challenge giants. The idea was that creativity, not capital, could win attention.

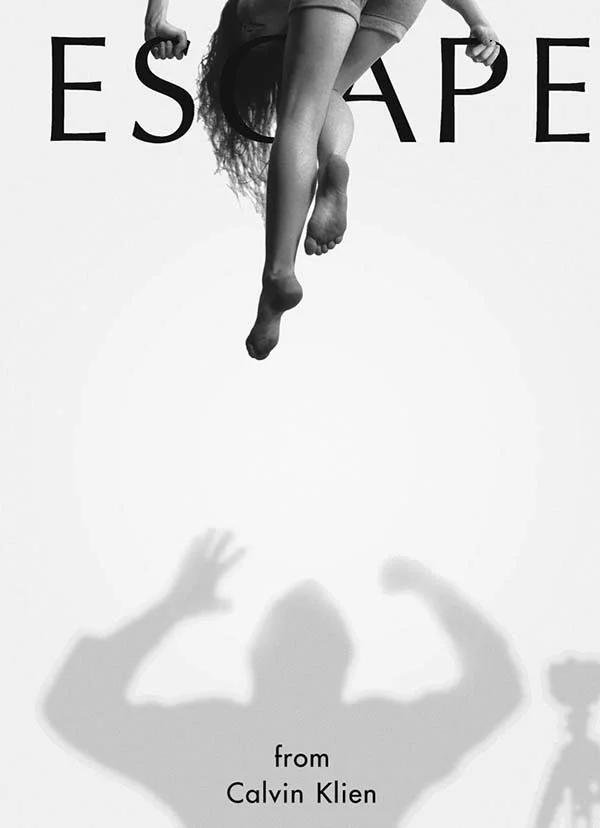

But long before Levinson put a name to it, the practice already existed. The Situationist International called it détournement — the art of hijacking dominant messages and twisting them to expose their absurdity. In the 1970s and 80s, culture jammers like the Guerrilla Girls or the early Adbusters movement pasted over billboards, edited magazine ads, and used the visual language of capitalism to sabotage it from within. Guerrilla marketing was born not in boardrooms but on the streets, out of protest, parody, and a refusal to play by the rules.

Four decades later, those tactics have resurfaced in an unlikely arena: the fight against billionaires.

Across London, parody posters have appeared overnight — “Tesla: the Swasticar,” “Autopilot for your car. Autocrat for your country.” The campaign, launched by a UK collective called Everyone Hates Elon, has turned guerrilla marketing back into what it once was a tool for dissent. Their posters mimic real ads, printed on the same glossy stock, slipped into bus shelters and billboards without permission. The stunts are cheeky, ephemeral, and politically loaded, exactly what Levinson meant by “shock value per square inch.”

And yet, this isn't marketing at all. It's anti-marketing, a culture jam aimed at the cult of personality that surrounds figures like Elon Musk. The collective's message isn’t "buy this” but “look closer.” Their recent "London vs Musk” event, which invited participants to literally smash up a Tesla in an industrial lot, blurred the line between art, protest, and catharsis. The whole thing was captured on camera, splashed across the press, and debated online for days, a masterclass in how to hijack the media cycle with nothing but fury, humour, and a sledgehammer. (Read more on The Guardian)

Tesla: the Swasticar,” The campaign, launched by the UK collective called Everyone Hates Elon.

They're not alone. The British group Led By Donkeys, best known for projecting political lies onto the Houses of Parliament, recently drove a Tesla along a Welsh beach to carve the words “Don't Buy a Tesla” into the sand, a 250-metre message visible from the air. (Coverage via Business Insider)

Days later, they unveiled a Glastonbury installation featuring cardboard cut-outs of tech billionaires queued for a rocket under the line “Send them to Mars while we party on Earth.” It was witty, defiant, and utterly shareable, everything traditional advertising dreams of being.

What connects these campaigns is not just their visual language but their intent. They reclaim the grammar of advertising — the fonts, the framing, the bold copy — and turn it against those who normally control it. Like Brandalism's climate interventions or the feminist poster actions of the Guerrilla Girls, they remind us that public space is not neutral; it’s a canvas, and it’s political. (Learn more about Brandalism)

Guerrilla marketing, in this sense, is not a trick for startups but a language of resistance. It thrives on surprise, uses humour as a weapon, and treats attention as a commodity. When it works, it feels alive, unpredictable, slightly illegal, and undeniably human. And that's what makes it so potent at a time when most advertising feels automated to death.

For independent creators and small brands, especially those driven by values rather than venture capital, the lesson is clear. You don't need to mimic the scale of the giants; you need to subvert their tone. Find the cracks in their narratives and plant something unexpected there. The best guerrilla work doesn't just sell; it talks back.

Sometimes, the most effective campaign isn't the one that asks people to buy; it’s the one that encourages them to look up, laugh, and question who’s really buying whom.